Deadly intersections and unsafe streets: America’s worsening pedestrian problem

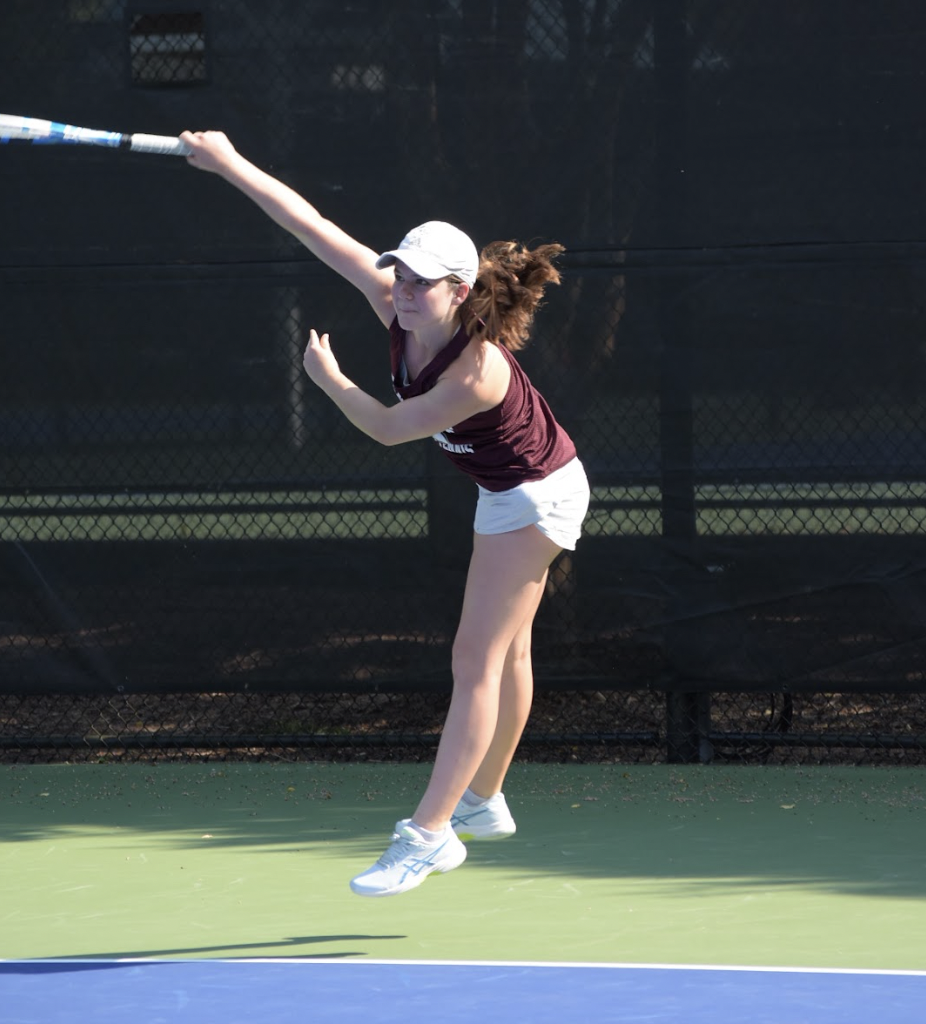

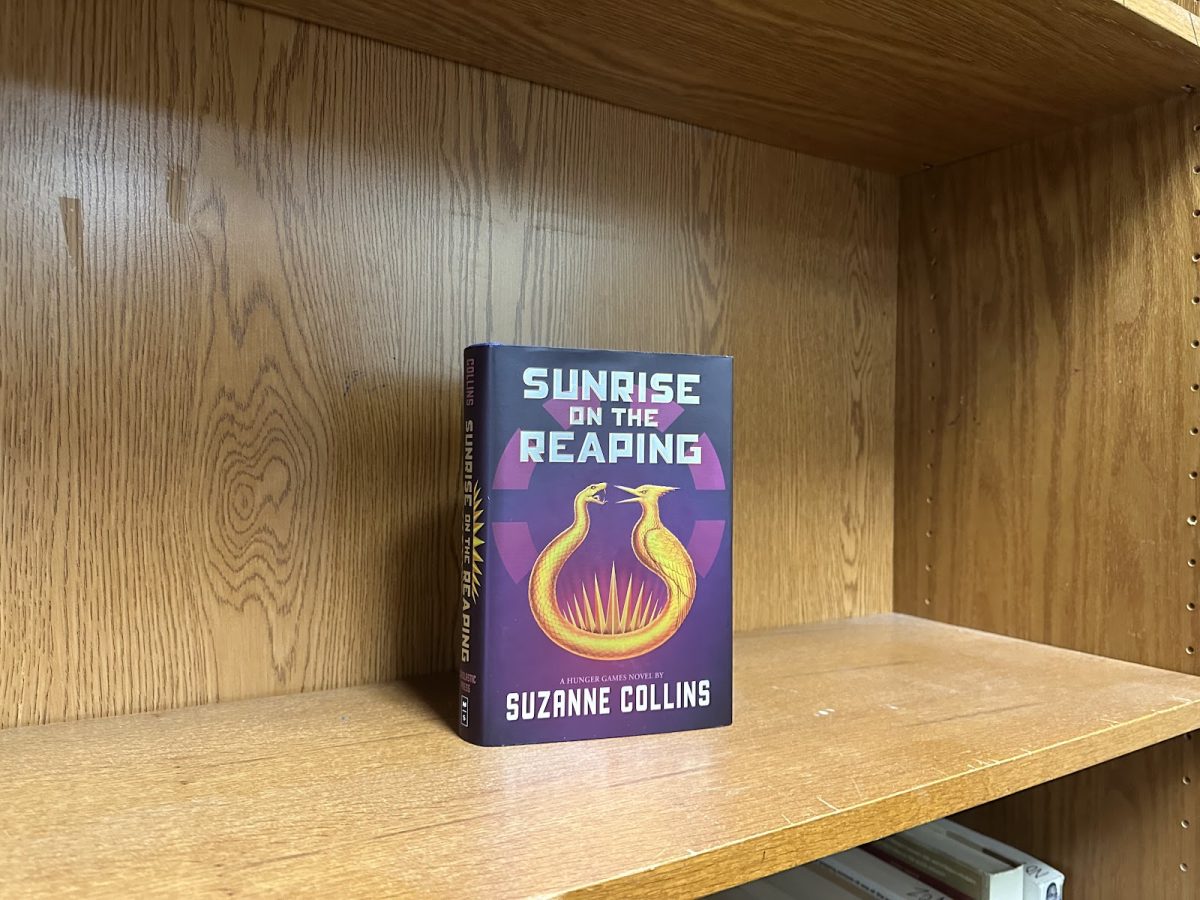

Intersections, like the one pictured above, are especially deadly for cyclists and pedestrians who may not be noticed by oncoming vehicle drivers.

May 4, 2023

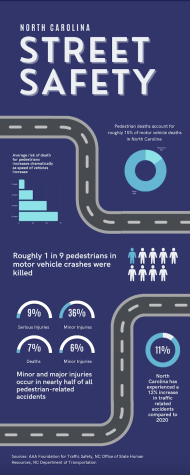

In late March, a vehicle collision near Durham killed cycling-enthusiast John Allore. The accident, which occurred on a narrow road with little shoulder area for cyclists, isn’t an anomaly. The North Carolina Department of Transportation estimates that roughly 150 pedestrians and 16 cyclists are killed in collisions with motor vehicles annually.

Such collisions are becoming increasingly commonplace in the United States, reflecting a national trend of surging pedestrian deaths. Walkability analysis site WalkScore collected data on 52 cities in North Carolina and produced an average walkability score of 26 out of 100. The score places North Carolina among one of the least “walkable” states in the country.

BikeWalk NC board member Heidi Perov Perry works with the organization to promote the use of sidewalks for transportation. “Fifty percent of all trips in the US are under three miles,” said Perry. “Those trips are not done by car, because they don’t feel safe.”

An avid cyclist since college, Perry believes government inaction is a primary cause behind the issue. “I think that most states are very reluctant to make anything less convenient for somebody who’s driving, and so they will not put a bike lane on a road where they want to have an extra car lane,” said Perry.

Perry noted that one of the most frustrating aspects of road designs is when bike lanes suddenly end. “It would make getting somewhere a lot harder, [and] this is where a lot of [accidents] happen,” said Perry, referring to sudden bike lane endings, which frequently force bikers to merge onto the main road. As a result, merging accidents increase– a study conducted by the Association of the Advancement of Automotive Medicine found that sideswipes were the most frequent cause of accidents.

At the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) Highway Safety Research Center, Stephen Heiny works with the National Center for Safe Routes to School in raising awareness, leading research and promoting youth road safety.

He holds a master’s degree in City and Regional Planning from UNC-CH, and specializes in transportation planning. “Sidewalks are generally your first step at creating a safe space because they create a separate space for pedestrians [and] for people that are walking with sidewalks. You [want] to think about where they’re going to interact with cars,” said Heiny.

“It’s the law in the state of North Carolina that bicyclists ride on the road and generally, the more you can separate lanes to actually create a barrier between cars and bicyclists, you’re going to create a more protected area for cyclists to travel,” said Heiny.

Heiny claimed that certain areas require additional planning, including school zones where students walk and bike to school. “A lot of the things that we think about for traffic safety would apply in the school zone as we’re looking at extra volumes of people arriving at the same time,” said Heiny.

He emphasized creating safe areas for students to navigate, especially in carpool areas. “[We want] pedestrians and bicyclists to cross the street to get to where they need to be and allow for those that have to arrive on the vehicle to get there and keep it separate,” said Heiny.

Funding for improvements is a fundamental issue that organizations have long struggled with, preventing increased accessibility and safety designs. “To make them more accessible, we need to put more money into building more sidewalks and trails and bike lanes,” said Perry.

North Carolina enforces a state-wide ban of funding for standalone bike and pedestrian projects, making it difficult for organizations to advocate for changes in road infrastructure. Perry explained that the only feasible way for organizations to obtain funding for road projects is through federal grants, which requires a 20% match from the filing organization.

“That means that places that don’t have the resources to come up with a 20% match can’t accept any federal funds,” said Perry. “We’ve been trying to change it since 2013. They haven’t done it yet.”

Heiny agreed and said that urban planners are often forced to prioritize certain projects over others. “It can become quite complicated how these decisions get made, but a lot of it is limited funding and where to apply it,” said Heiny. “Sometimes it’s just a matter of really thinking about what the roads in a city are for and who they serve.”

Surveys conducted by the Department of Transportation reveal that the leading cause behind lack of pedestrians and cyclists lies in safety concerns and lack of routes. The lack of pedestrians and cyclists further discourage governments from investing in developing safer roads.

However, Heiny sees a promising future in increasing walkability by encouraging current students to appreciate the benefits of cycling and walking. In collaboration with local elementary and middle schools, Heiny helps to implement national Walk and Bike to School Day, which took place on May 3, 2023.

“It’s a chance for school to kind of make an event out,” said Heiny. “Think about how students are going to get to school that day, [in] whatever active mode that they can use, and maybe [it] starts to become a regular thing.”

Heiny explained that coordinated events encourage citizens to actively participate in using the infrastructure of their communities. “It’s always a great opportunity to start a habit or realize that it’s not too hard to actually ride a bike to get down to the store or walk to get somewhere,” said Heiny.

Despite the progress local organizations have made, Perry voiced her frustration regarding the situation and remained insistent upon the need for further progress. “It’s kind of a catch-22, right?” said Perry. “Nobody’s using it because there’s no crosswalk there. [We] really need to put some of our Department of Transportation funding into bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure.”

Teddy chen • May 6, 2023 at 9:26 pm

Good job Peggy 🙂 very serious but also calm I like it!!!!