It’s week one of the National Football League (NFL) season and the sold-out crowd of 82,500 fans in MetLife Stadium is silent. After just four offensive plays, star quarterback, Aaron Rodgers, is on the ground surrounded by trainers. This injury re-opens the discourse on playing surfaces throughout the league.

Uses of artificial turf began in 1965, when the Houston Oilers moved into the Astrodome. The first iteration of the turf was simply a thin carpet over hard concrete, a very uncomfortable playing surface for the players. For the owners, however, the turf was a great investment. The turf was expensive upfront but required little to no maintenance after installment. Turf requires no water and no mowing, lowering costs for the owners who strive to maximize their profit.

The turf fad caught on, and by 1990, over ten stadiums had artificial turf, much to the players’ dismay. Player injuries significantly increased due to the concrete beneath the field. Many players suffered hip and knee injuries, mainly due to the hard playing surface. Luckily, after the turn of the century, companies began developing better turf. This improved turf was introduced into the NFL with the installment of FieldTurf.

First introduced to the NFL in Seattle, the Seahawks installed FieldTurf prior to the 2002 season. This new surface included sand and rubber, hoping to provide shock absorption and better mimic natural playing surfaces. Currently, six NFL stadiums use FieldTurf, Gillette Stadium (Patriots), MetLife Stadium (Jets/Giants), Ford Field (Lions), Mercedes-Benz Stadium (Falcons), Bank of America Stadium (Panthers), and Lumen Field (Seahawks).

Green Hope football player, NBC All American and SWAC All-Conference nominee, Ian Hemilright (‘25), has played on FieldTurf while competing at Duke’s practice football field. In an interview with the GH Falcon, Hemilright spoke on his experience playing on FieldTurf stating, “The main difference between grass and [the turf] was the traction. I was able to get a lot more grip to my cleats. When I would plant my foot in the turf, the movement of [my] foot was very restricted.”

Many other types of turf have been developed recently such as Matrix Turf. Matrix Turf has also risen in popularity within the NFL. This past off-season, the Dallas Cowboys and Tennessee Titans installed Matrix Turf, raising the total of NFL stadiums with the surface to five. Matrix turf is much thicker than previous iterations of artificial surfaces. It has a thickness of 2.25-2.5 inches compared to the 1.75 inches for FieldTurf and the 1-inch thickness of AstroTurf.

Though there have been stark improvements to turf, NFL players still feel as if the turf is not as safe as natural surfaces. The main complaint with the turf is the lack of “give”, or mobility for their lower limbs when making explosive movements. When asked about the lack of mobility while playing on turf, Hemilright responded, “The explosive movements don’t seem more dangerous on the turf, in fact, I like that it gives me more grip while I block people and when I need to run.”

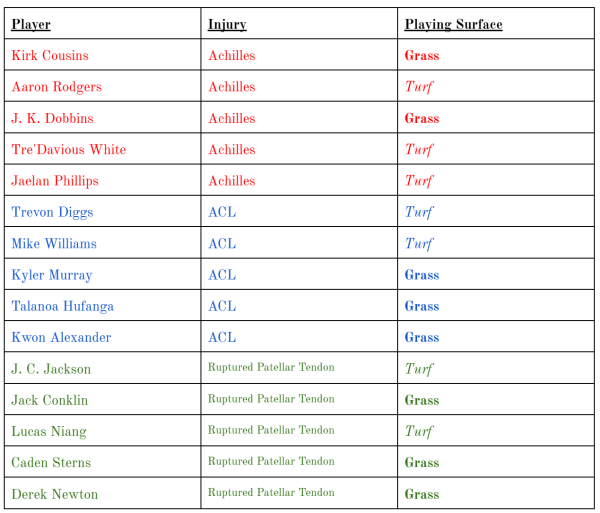

This lack of give is often seen in severe lower body non-contact injuries, especially torn achilles tendons and torn anterior cruciate ligaments (ACL). These devastating injuries require season-ending surgeries and months of rehab. As these injuries became more frequent, the union that represents NFL players, the NFLPA, began investigating if the increase in injuries was due to artificial playing surfaces. In a statement released by NFLPA president J.C. Tretter, stated that the difference in injury rate (calculated by injuries per 100 players-plays) between synthetic and natural surfaces had increased from a difference of .001 in 2021 to a difference of .013 in 2022.

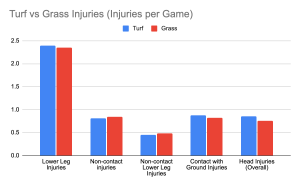

While there are claims of lowering injuries from the use of this new technology, there has been contradicting evidence given by Spots Info Solutions (SIS), a partner of the NFL. After tracking every injury in NFL games for the last six seasons, SIS deemed that non-contact injuries happened more often in games on turf fields than they do on grass fields, refuting one of the NFLPA’s main complaints about the turf. SIS’s data did show that head injuries, a growing concern following many players developing CTE, occurred more frequently on turf fields.

The next time a star player suffers a season-ending injury on a turf field, players and the NFLPA continue to push for natural grass surfaces to be uniform throughout the league, but owners and the NFL will try and resist. This will likely lead to a decade-long disagreement, one that might never end.