The toxicity of academic perfection

Teens push both their bodies and minds aiming to live up to the high standards placed on them.

November 14, 2022

The clock hits 2 a.m. as an overworked teenager stares at the empty document that should be their English paper. Fried with exhaustion, the singular thought clouding their mind is sleep, yet they force open their drooping eyes. Even as the student’s head swells with a sharp migraine, they take a deep breath in preparation for the long night ahead. There is no other choice; for they cannot fail this. They cannot be a failure.

While some may view this as an exaggerated narrative, this is the everyday routine for a large portion of students. Now, more than ever, high schoolers place an unhealthy importance on academia, diminishing themselves to nothing more than a “good student.” As a result of this becoming their primary characteristic, the struggle to develop a unique sense of self is overlooked among teenagers.

Contrary to the beliefs held by high schoolers, failure is an essence of learning. It allows the understanding, analysis and correction of mistakes. Learning to fail is a part of life, and failing is a necessary skill to enter the so-called “real world.” Unfortunately, the acceptance of coming up short of expectations is one aspect the average student does not possess.

Modern-day high schoolers don’t know how to fail, and increasing detriments to their physical, social and mental health is not helping them handle it.

Given that there is such emphasis placed on receiving perfect grades, it is no surprise that teenagers base their identity on a report card. It’s saddening that young adults who hold deep understandings of strenuous subjects struggle to gain any understanding of who they are as individuals.

The problem remains that schools are putting unnecessary emphasis on academics while failing to give teenagers a well rounded high school experience, something critical to development and future success.

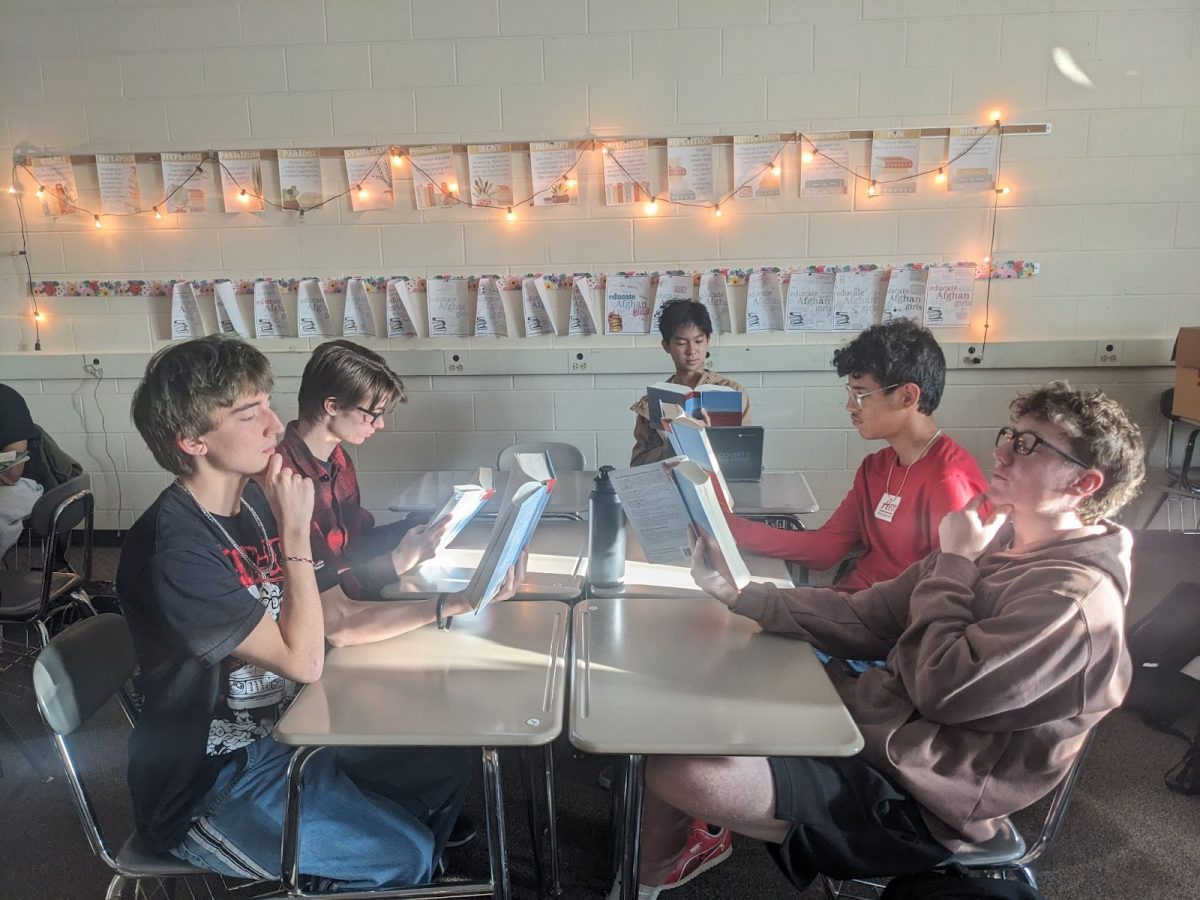

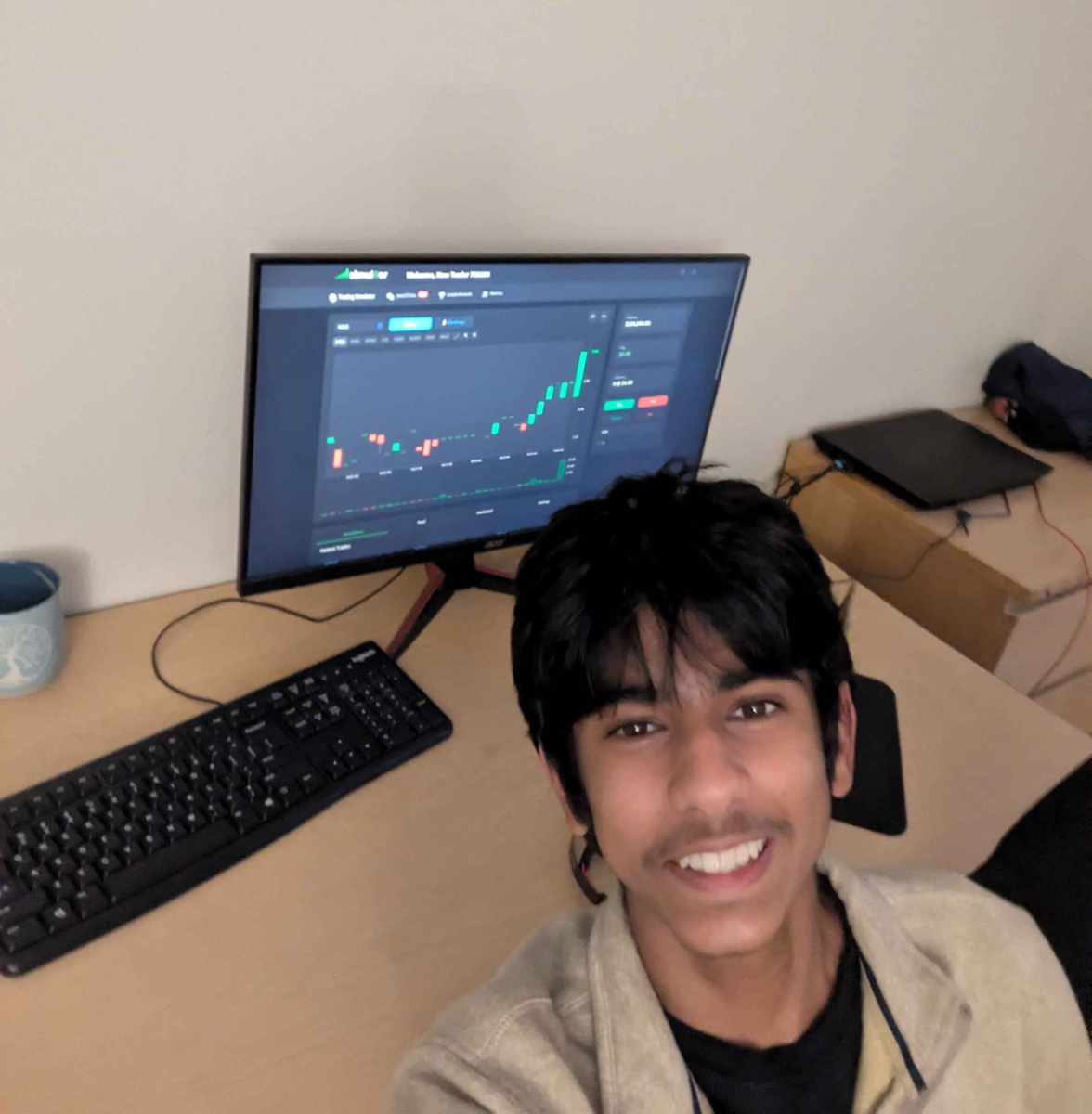

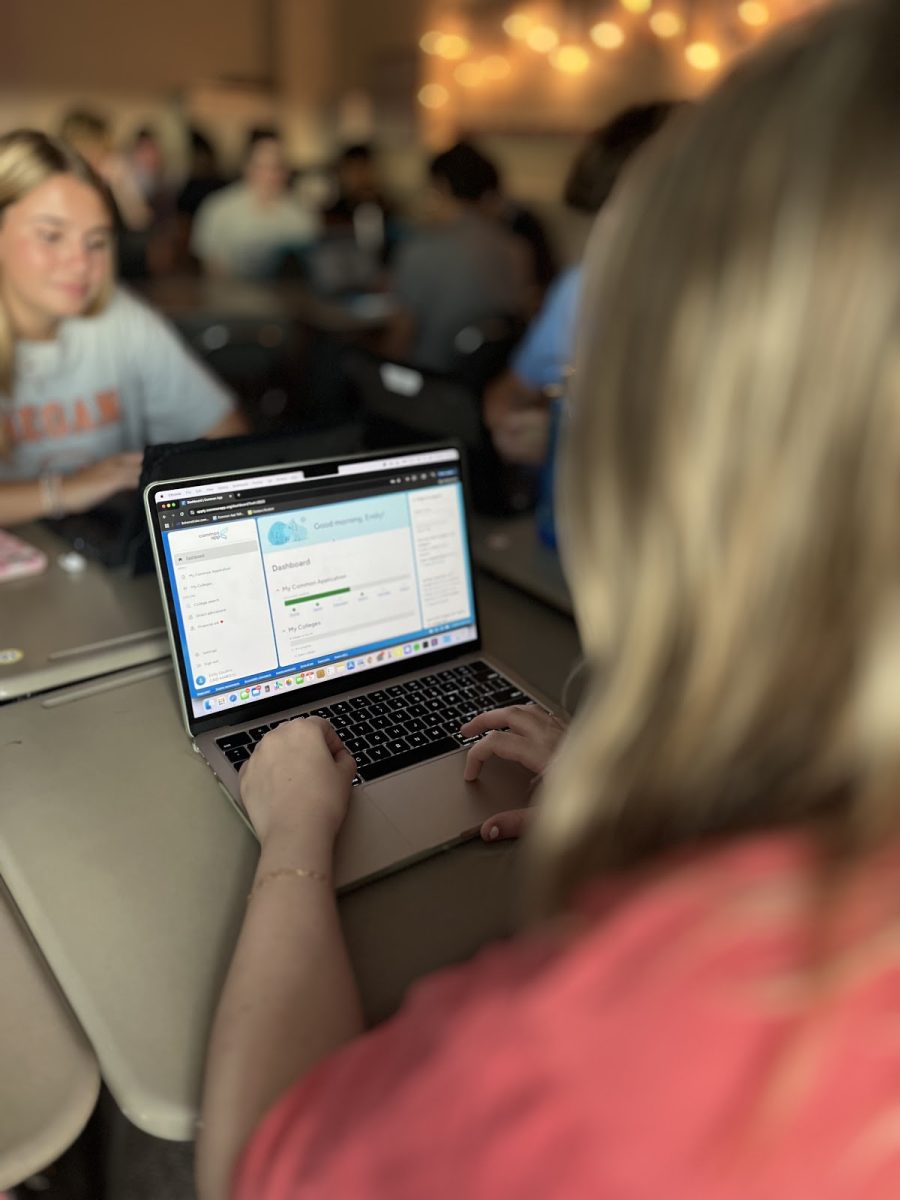

What should lead to camaraderie amongst peers has evolved into ugly competition, a race to the ultimate goal: college. High schoolers continue to let this collegiate tunnel vision absorb them. Oftentimes, this damage is seen as hard work and applauded by parents, teachers and peers, but at what expense?

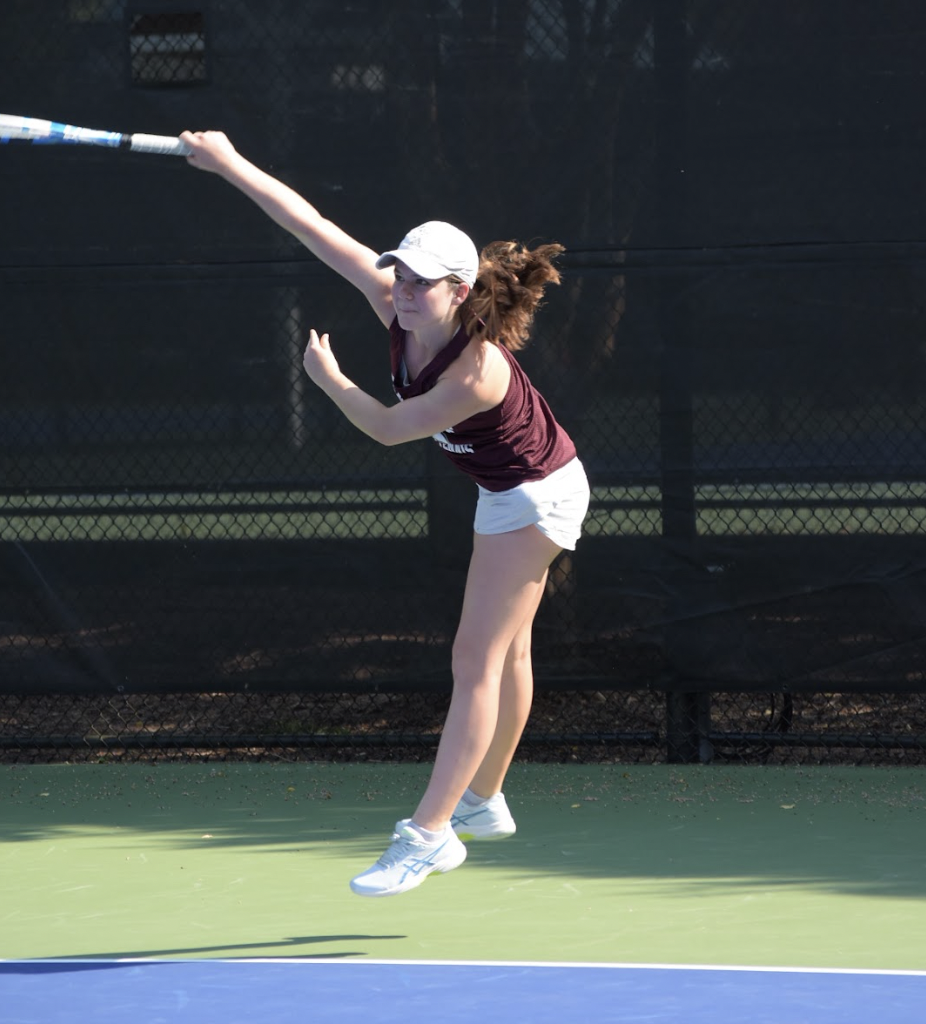

The impression has been developed that a degree from a top university will carry a person to success. This fails to take into consideration that if social skills are underdeveloped throughout high school, a person is unlikely to thrive in a workplace environment. Networking, leadership and conversational capabilities are all necessary in a professional setting, and it’s often these skills that stand out to employers. However, since social activities aren’t held to the same level of importance as academics, these skills remain underdeveloped in young adults.

A contributing factor in hindering social abilities are mental disorders which have been on an upward trajectory among students in recent years.

In an article regarding this issue, the Newport Institute stated, “Academic pressure can lead to depression, anxiety disorders, or high-functioning anxiety.” An NYU research study went on to support this stance as well as elaborating on research that found highly-pressurized students resort to increased substance abuse. Recently proving this assertion comes from North Carolina State University where four students have committed suicide since the beginning of the 2022 school year.

These disorders and harmful coping mechanisms will not be cured with a Harvard acceptance letter. Instead, they will worsen and end up becoming more detrimental than a singular failing grade.

Teenagers fail to understand that the expectations placed on them today are ones previous generations have not had to deal with. Colleges have become more exclusive, resulting in students taking drastic measures to ensure acceptance. According to The Atlantic, “ridiculously low acceptance rates have become the norm: 5 percent at Stanford University, 10 percent at Colby College, and 12 percent at Vanderbilt for fall 2020. But selectivity is something of an illusion, stressing students out and leading them to needlessly apply to multiple colleges when they can enroll in only one.”

Although encouraged by colleges, it is critical to understand that an all-AP schedule, combined with time-consuming extracurriculars, is not safe. These choices account for nearly all 24 hours of the day, leaving no room for rest. Placing this near impossible standard on growing kids is wrong. Schools gain positive feedback from rising GPAs, while the decline in students’ mental health is left in the dark. At the end of the day, a 4.0 is just not worth it.

Schools have gone on to promote this toxicity for years and it doesn’t seem that they will stop any time soon. Students need to take initiative, realizing that there is more to learn than what is present in the classroom. Slaving away for academic validation while depression and anxiety take over one’s brain is an absurdity.

A person is not a number. Reducing oneself to nothing more than a GPA or class rank is an awful practice. The cycle needs to break and schools need to realize that a good grade does not always equal a good education.

Falcon Reader • Nov 15, 2022 at 7:03 am

Aarushi – this is a well-written and thought-provoking article. It inspired a lively and lengthy discussion in our household last night about the topic. It’s easy to see that academic toxicity is a problem; it’s much harder to identify the true source of the problem. While high schools are an easy and obvious target, I wonder if identifying the true culprit is more difficult and nuanced. Do the students themselves deserve any of the responsibility? How about their families? Colleges? Societal pressures? It’s an interesting topic for sure, and it seems there are a lot of variables at play. Thanks for writing the article.