Often, when high school teachers assign a group project to a class, students react with groans and eyerolls. Group work is a good idea in theory– it’s meant to encourage teamwork and communication. In reality, however, group projects are inefficient, frustrating and widely unpopular among students. It seems like no one likes group projects, so why do teachers keep assigning them?

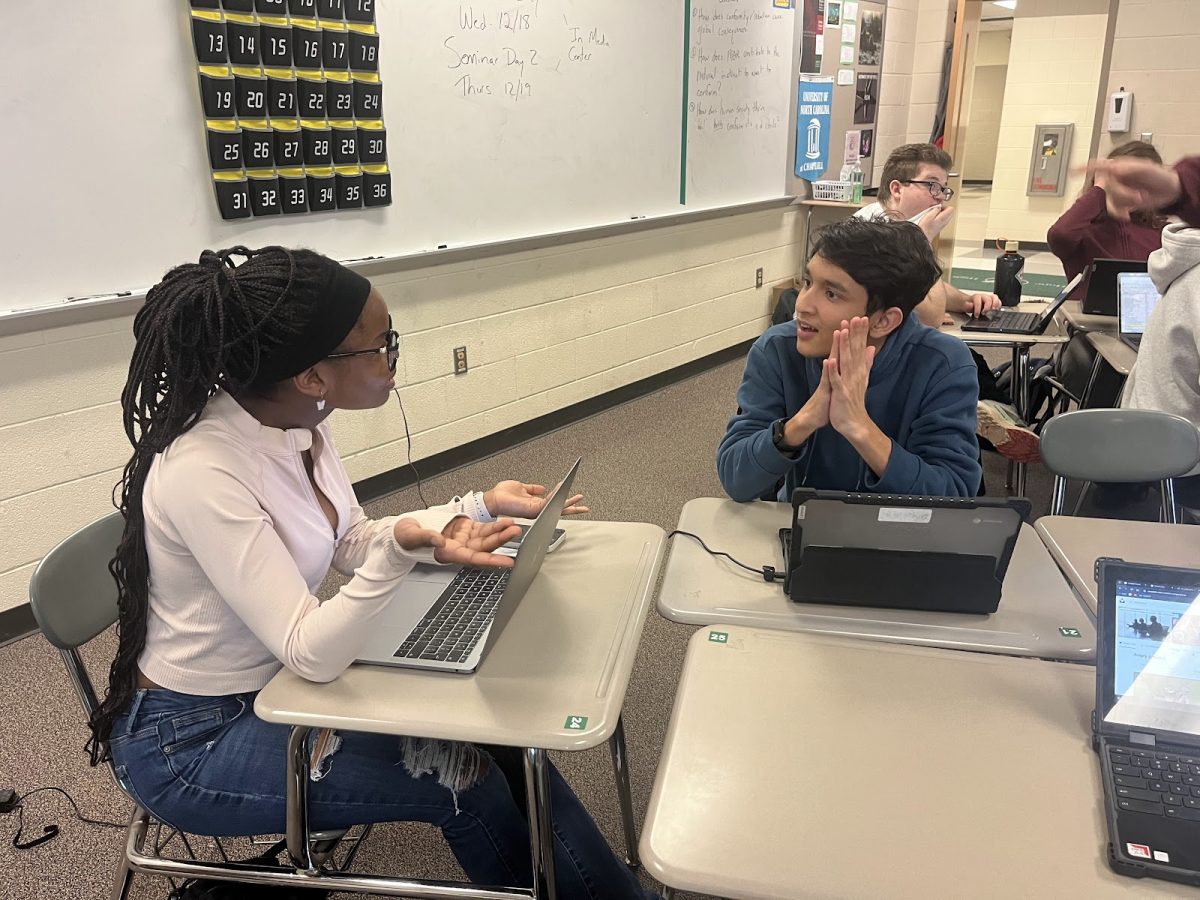

Group projects are supposed to foster collaboration, but can often do the opposite when students divide and conquer the work. Most high school group projects wind up as individual assignments because everyone ends up working on their own part, defeating the purpose of group projects. When this happens, the assignment is not a group project but working alone with other students.

Students would rather complete the portion of the project that they’re comfortable with than jointly work with other students, and therefore they learn nothing new about the course material or effective communication skills.

Another factor that hinders group collaboration is clashing perspectives. Varying ideas and work styles sometimes blend to make a great project; other times, they cause conflicts that thwart progress and make the project more stressful for everyone involved. Additionally, working in a group can stifle creativity, because many students are afraid to share unconventional or bold ideas with their peers out of fear of rejection.

What’s worse than a lack of group collaboration, however, is a lack of group participation. Group projects gather students with differing levels of dedication, ambition and competence. Often, one or two people typically end up taking the brunt of the work and the indolent students get a free ride.

Gabrielle Brown (‘25), like many students, is not a fan of group projects. Brown explained, “Usually, unproductive members don’t face any consequences because their group mates are too afraid or too nice to report them to a teacher.” She elaborated on her past experiences in group projects, stating “In the past, I’ve avoided reporting poor behavior from people in my group because I didn’t want to be labeled as ‘overdramatic’ or as a ‘tattletale.’ ”

Although there is typically varying amounts of effort within a group, teachers usually grade group assignments with a collective score. This can result in frustration in students who did their part in the project, while members who contributed less receive a grade that they may not deserve.

To avoid the issues that arise from students’ differing dedication levels, teachers often implement peer evaluation systems within group projects. However, these systems do not always effectively resolve these issues. Many students, due to biases towards their friends or hesitation to confront others, shy away from being honest with their peer evaluations.

Kripa Vaidya (‘26) reflected on one of her experiences with group projects. “In a group project for biology, my group members didn’t bother to do anything, so I ended up having all of the work piled on me.”

Vaidya raises a possible way to alleviate this pressing problem. “If we absolutely have to participate in a group project, students should always be allowed to pick their own groups,” she said. “If you already know your group members, it makes the process of a group project a lot less awkward. It also minimizes the likelihood of people not pulling their own weight.”

While group projects are meant to teach teamwork, they often lead to unfair grading, an uneven distribution of tasks and feelings of stress. If the focus is shifted to alternate learning strategies that inspire both joint effort, cooperation and accountability, then classrooms will be much more efficient. Since group projects do more harm than help, they should be re-evaluated as a cornerstone of education.