‘Food for thought’ is a column that introduces readers to pressing issues in our world today and the people who are tackling them head-on.

How do we grow enough food to feed booming populations without degrading the little natural capital we have left? This is a question that natural resource management specialists and agronomists ask themselves frequently, with ramifications impacting nearly everyone.

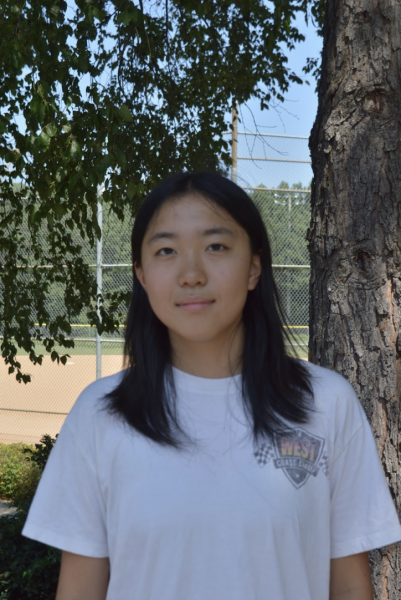

Some would say the solution lies less in the need to create more food than in creatively using the food we already make. Essentially, it’s a question of how to optimize resources and mitigate food waste, a question that Arielle Lok seeks to answer.

The 22-year-old newly minted McGill University graduate already has an impressive list of achievements under her belt: she helped write the Canadian Children’s Charter in high school, founded her school’s “Lettuce Club” – a tradition where hundreds of students race to finish a single head of lettuce and during her last years of college, founded Peko, an “ugly food” startup venture that was acquired in February by Fresh Prep, one of Canada’s largest sustainable meal kit services.

Lok was born in Hong Kong, a city she describes as “super, super dense” with widespread walkability. When she was nine, her family moved to Calgary in Alberta, Canada. The transition was less than ideal for Lok, who described her dislike for the city’s easygoing and slow way of life. It also, said Lok, served as the primary motivation of her working towards attending McGill University – whose Montreal campus is much more similar to that of big cities – on a scholarship.

“Calgary is like Houston, Texas, maybe like Houston and Austin, Dallas, all combined into one where it’s like really suburban, but also like there’s a city but it’s not that great,” she said. “So I work as hard as I can to leave the city. And I think that’s what really shaped the person that I am today.”

Attending McGill was a dream come true for Lok – that is, until the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic is an experience that she described as not only isolating but also revelatory. “[E]verything went online. And once that happened, and I was away from school, I just kind of realized how much I didn’t like school. And I really miss like the feeling of like, starting my own thing,” said Lok. “And that’s why Peko ended up coming.”

Peko was the brainchild of Lok and her co-founder, Sang Lê. They met through a mutual acquaintance who connected them in a message chat. They initially met through Zoom and ended up discussing their interests for over an hour. They eventually found that a business model like Peko allowed them both to use their strengths.

“And it was just a pure coincidence that our skill sets were so different,” said Lok. “For me, like all the policy work that I’d done before was related to kids under the poverty line.”

Then, the hard part came: reaching out to farmers who would be willing to source them with “ugly” and rejected produce. “I spent a whole month talking to as many farmers as I could… from day one which was May 1. We got all the way to doing our first deliveries on May 30. Because the whole time [we were] talking to farmers [and] getting our supply chain set up and then Sang Lê was [leading our] marketing.”

Peko makes use of “ugly food,” a term that refers to misshapen or discolored groceries that are still safe to eat, but their appearance leads main grocery chains to reject them from farmers.

“[Ugly food is] a total marketing thing,” said Lok, explaining the triviality of judging the edibility and health of crops purely from aesthetic appearance. She also stressed that supply and demand fluctuations make excess food waste. “[Sometimes], you just have like a ton of tomatoes that you can’t like offload, and all of a sudden it’s gonna go bad unless you can find a buyer … a big part of Peko [is that we] remove it for them.”

In an era where computer science and technological careers dominate many prospective innovators’ dreams, agricultural fields are often left behind. As Lok conversed with various farmers, many were especially willing to impart advice and aid the young entrepreneur in her endeavor. “I just got to know the farmers well. A lot of them again, were receptive because I was so young,” Lok said, describing farmers’ eagerness to see young business people tackling relevant food-related issues. “So they’re just like, ‘Not a lot of people are interested in this industry.’”

In regards to the lessons that she learned from founding and nurturing Peko’s growth, Lok highlighted the importance of cultivating a supporting and invigorating network of peers. “I think it’s really important to surround yourself with people who are also like you.”

She detailed the various collaborators, co-workers and acquaintances who wore various hats during her journey. Some merely helped set up meetings with potential investors or helped her refine her pitch, while others lent her warehouse space or helped deliver grocery packages.

“I don’t think I would have started a company if like it wasn’t for the pandemic and I met a bunch of people on Twitter who were also students studying companies and like being in their presence, like really made me want to do it too,” she said, calling attention to the importance of her friends and collaborators.

We are what we eat – and Lok claimed that we are also who we spend time with. “You are kind of an amalgamation of the seven closest people to you. Like all of my best friends now are founder people – they have also started their own compan[ies] really young, and I think because of that I was very, very motivated and I feel like I have a really good support system.”

In the future, Lok will be joining a climate startup to develop enhanced rock weathering. “[It’s] a way of like engineering soil to take in and sequester more carbon,” she said. “So you’re effectively removing carbon from the atmosphere.”

Although she has reduced her involvement in Peko after its acquisition, Lok is insistent on confronting the climate-change challenges that the world needs solving – and encourages everyone she meets to do so too.