Is “Cocaine Bear” feminist?

A deep dive into the Bechdel test and how the roles of women are portrayed in 21st century media.

The Bechdel test is used as a barometer to measure the depth of female characters in movies, books and other cultural outlets.

Two women are strolling down a city sidewalk. “Wanna go see a movie?,” one asks. “Only if it passes this rule…,” responds the other.

She proceeds to explain her three requirements that a movie must satisfy: It has to have at least two women in it (1) who talk to each other (2) about something other than a man (3).

The two women, discouraged, trudge home and dismiss seeing a movie entirely. This scenario is the basis of a 1985 comic strip, “The Rule”, by Alison Bechdel.

“The Rule” spiraled into a renowned phenomenon sparking conversation involving the portrayal of women in media. Later dubbed the Bechdel test, it served as a barometer to measure the depth of female characters. “The Rule” can be applied to forms of media ranging from books to video games.

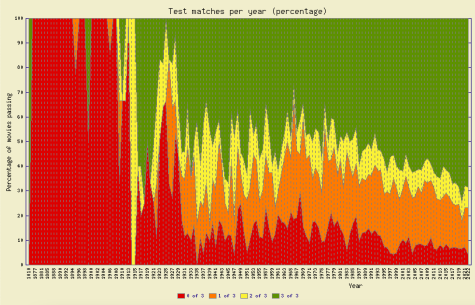

According to bechdeltest.com, a website designed for movie goers to update a continuous movie database, 5594 out of 9802 recorded movies pass the test. Over the past century, the percentage of movies fulfilling all three requirements of the test has skyrocketed from 17% to 57.7%.

These numbers, however, are considered unreliable. The three rules are arguably vague. The basis of what qualifies as a conversation between two female characters can include inconsistent interpretations. A user who updated the Bechdel database claimed Elizabeth Beth’s “Cocaine Bear” passed the Bechdel test on the grounds that the bear was a female, although it may include questionable portrayals of women. So no, Cocaine Bear is not outright feminist.

“Weird Science” (1985), a story focusing on two teenage boys who create their own woman who describes herself as “leggy, buffed and brainy,” is another example of the test’s shortcomings. The movie passes the test even though the woman has character traits only meant to appease her male creators.

While the Bechdel test is inherently subjective, it still exposes Hollywood’s unintentional bias. Before gaining popularity, representational imbalance would have easily gone unnoticed. A surplus of strong female characters have been created, especially in the last 50 years–ranging from G.I. Jane to Wonder Woman.

Every princess is expected to find her prince, but the Bechdel test reenvisions the stereotype of female motives and portrayals in movies. Screenwriters should be held accountable to create characters that enrich humanity, not to fulfill outdated standards. American youth should grow up regularly seeing strong female characters who have a sense of purpose outside of the male gaze.

The staff of the GHFalcon would love a donation to help the journalism program at Green Hope continue to flourish. Many of our donations go to towards improving the materials that we deliver to you in electronic format. Thank you so much to those that are able to donate.

Sophia Melin, a pickle enthusiast, is a senior at Green Hope High School. Since two years old, she’s been a competitive dancer--- she’s carried this passion into high school too, serving as a president...