This is the first article in the “Roots and Remembrance” series, documenting efforts to revive interest in local history in the Cary area.

The most valuable stories aren’t always in the written word – they can be heard. Oral storytelling passes down rich generational tales that would otherwise be lost, and the Friends of the Page-Walker Hotel is doing just that.

Through the Cary Heritage Museum Oral History Project, members of the initiative chronicle the lives of “ordinary” citizens through recorded interviews. These are sent to the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill’s Southern Oral History Project (SOHP) for preservation. Recorded conversations date back to the 1970s, and are still used by researchers today.

Peggy Van Scoyoc, a key member of the initiative, has been a Cary resident for three decades and officially founded the project in 1998. She joined the board of the Friends of Page-Walker from 1997, and describes those older conversations as some of the most precious interviews from Cary.

Since the start of the program, Van Scoyoc and other participants of the Oral History Project have collectively interviewed over a hundred Cary residents. “[We do it to] learn about their lives; their memories, their local, cultural, state, national and world histories; and how all of that impacted, you know, the lives of everyone here in Cary. So that’s kind of where we started. And they just started telling fantastic stories.”

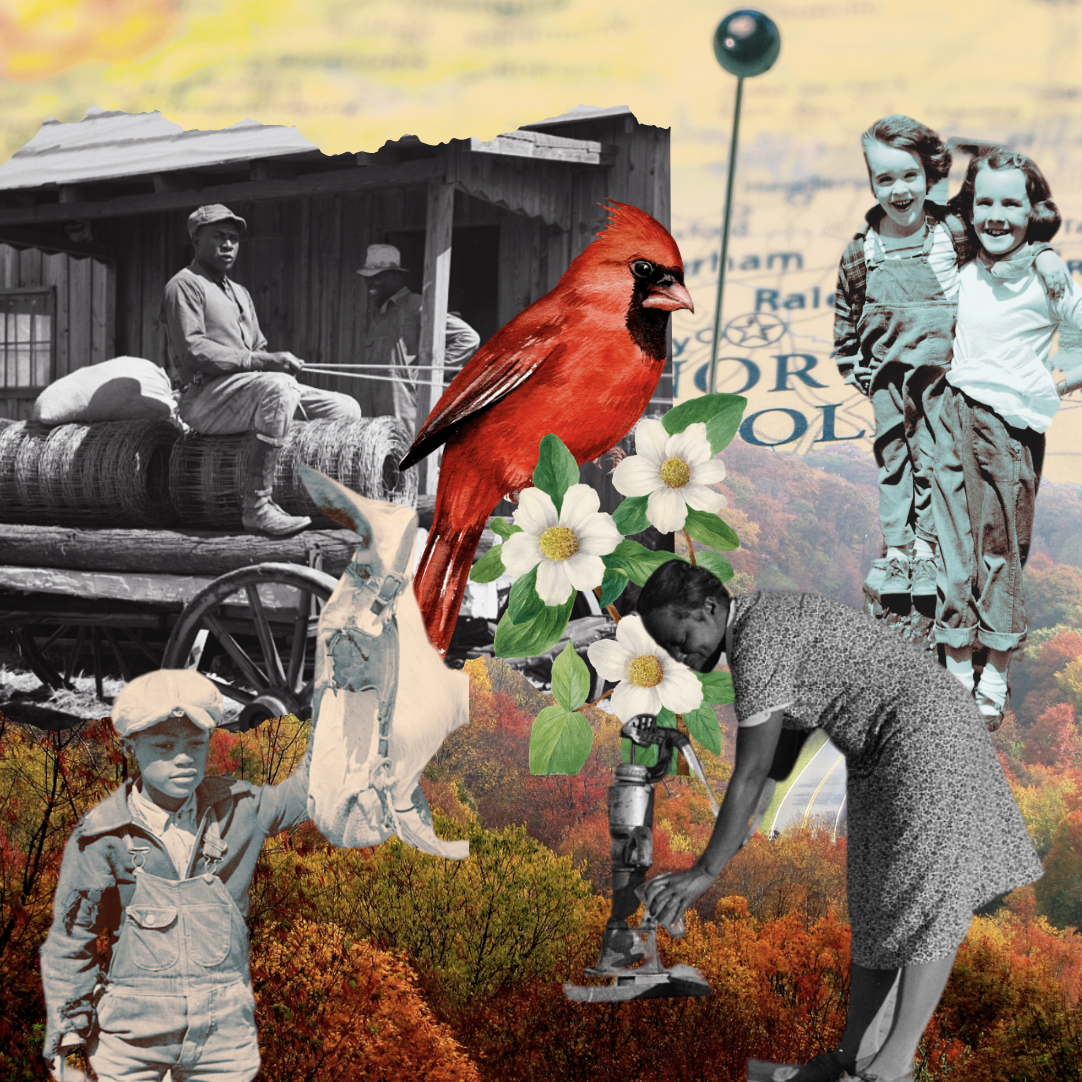

Because much of local history is passed down by word-of-mouth or through families, when key figures of the town pass away, their stories risk being lost. Van Scoyoc fears that pockets of history, such as the community services of African American churches and black perspectives during the segregation era, will be permanently forgotten in the understanding of Cary’s history.

“I think it’s so truly important to be able to [preserve histories], even though it’s not 100% perfect history and science,” she said. Scoyoc said that placing these recordings in locations like the The Wilson Special Collections Library at UNC-Chapel Hill means they will be available to researches for years to come. “But [we want] to get it as perfect as we can to a place like Wilson Library, so it can be researched and it is documented.”

Sophie To, a doctoral candidate at UNC-Chapel Hill, specializes in Asian American oral histories and is a member of the SOHP. As a researcher, she pulls on the work that historians like Van Scoyoc collect and emphasizes the importance of these recordings. “Preserving those voices, even after those people are no longer with us, is so important because people in the future generations can still learn from them.”

In particular, local history and oral history are closely intertwined ideas. At times, the primary source of the history of towns like Cary is from cassette tapes tucked in a dusty library. “Sometimes [oral histories] are the only – or the biggest source – of history that there is … [we use] that to the extent that we can with any possible artifacts or photographs or other objects from the past, and all of those together can form a really powerful story.”

As much as large-scale, national events are worthy studying, local history is too, To said. She explained how oral histories – where people candidly tell their stories, experiences and perceptions – uplifts the voices of historically marginalized communities.

“I think the local part of oral history is sometimes the coolest. Listening to [communities] is really important, because that can help shape local policies, whether that’s capital P policies for the town council or just policies at a school level or a neighborhood level.”

Van Scoyoc also introduces the importance of crafting future education institutions that engage youth. She elaborates on how if one doesn’t know anything about the history of their community, they risk underestimating the value of historical collection efforts. Scoyoc hopes to quell this issue by introducing more ways to engage younger children and students in learning about local, state and national history.

“[We need to] introduce more and more ways to engage younger children and students in learning about history, local history, state history, national history, and why that’s important, because we as a nation, as a state, as a city, have developed over time,” she said. “And if you don’t know anything about the history … that’s even more important.”

To also sees value in including a larger population to engage with oral histories. She sees a sense of hope in the up-and-coming historians she mentors at UNC-Chapel Hill. “A lot of my students are, you know, young. They’re 10, 15 years younger, and they are so interested in this, and sometimes they have insights that are even more in-depth than [mine]. I think it’d be really cool if something like oral history could be more in school curricula, and could be incorporated into more like history lessons.”

The takeaway, To explained, is that history isn’t just a thing of the past – it’s a way to understand the present. Social impact and historical preservation are intersectional ideas that can harness change.

“[V]oices of communities matters. The diverse voices of many different groups, many different people matter.”