As Rose Rosaleen (‘24) and Sarah Pazokian (‘24) experienced their first menstrual cycles in an elementary school bathroom at age 11, the thought of returning to school without access to feminine products served as a pivotal moment in both of their lives – a moment that ignited their determination to empower girls across the nation, one period at a time.

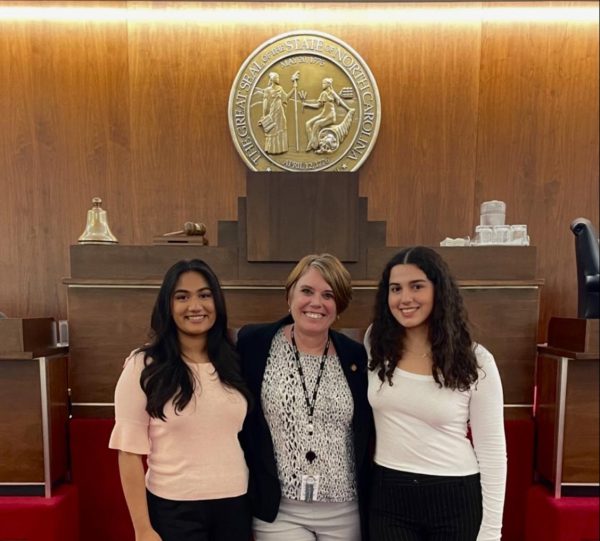

Period Project of North Carolina (PPNC) is a non-profit organization established in 2021 by Green Hope students Farah Rosaleen and Sarah Pazokian (‘24). It strives to provide and advocate for free menstrual products in North Carolina public schools. With over 120 PPNC ambassadors across over 15 Wake County schools, the organization seeks to destigmatize feminine hygiene and advocate for women in North Carolina and beyond. The pair has been featured on several news outlets including CBS, NBC, Spectrum News, INDY Week and North Carolina Health News.

In an interview with The GH Falcon, Pazokian provided insight into their motivation to bring PPNC to life.

“We saw that there was a need for period products. A lot of students didn’t have products available and had to go all the way down to the front office, which takes a lot of time throughout the day. It sent a message that female education just isn’t being prioritized,” she said.

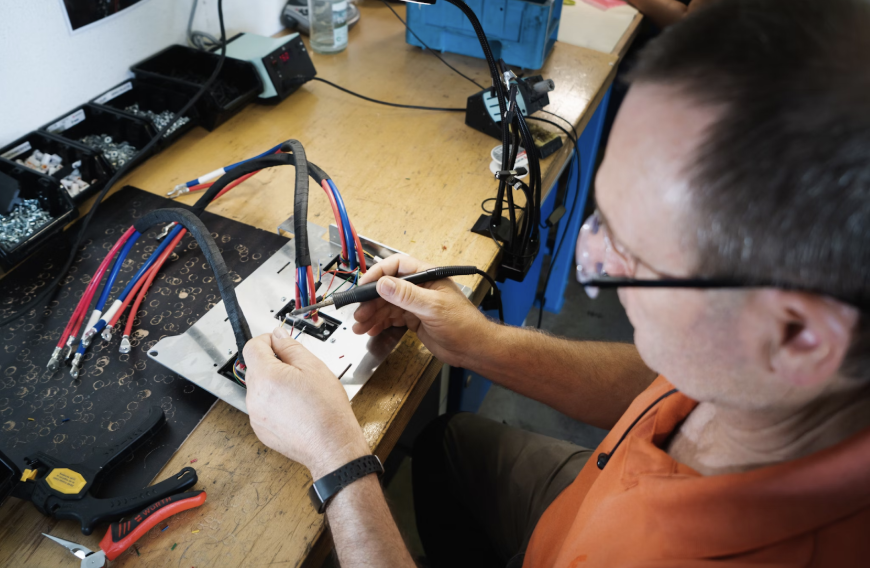

Rosaleen and Pazokian conducted a two week trial during the 2022-23 school year before fully implementing the dispensers in school bathrooms. Since then, Period Project has installed about 12 dispensers in each school that participates in the program, including Green Hope High School, Panther Creek High School, Apex Friendship High School and Lowe’s Grove Middle School, totaling to roughly 56 dispensers. The success of their dispensers, which help around 4,000 students and have received an enormous amount of positive feedback, prompted the founders to expand beyond their state.

In August 2023, Rosaleen set to broaden the impact of the organization to countries where menstruation is considered a taboo subject. She distributed packages containing menstrual products to 100 students at the Hazaribagh Girls’ Public High School in Dhaka, Bangladesh and delivered a speech on the importance of feminine hygiene in an effort to destigmatize periods around the world.

Rosaleen touched on the initiative, explaining the importance of addressing period stigma and poverty beyond her school community.

“In South Asian culture, menstruation has historically been seen as something that is dirty, especially in correlation with religion and culture,” she said. “Menstrual hygiene isn’t that great there and the girls aren’t aware that they shouldn’t be using pads or liners – and they don’t even know how to use them. Most of the time, they use rags which can lead to an increased risk of ovarian and cervical cancer.”

She also elaborated on her inspiration to educate the students on menstruation.

“I think they were surprised because they didn’t think I’d talk about something like this, but when I was handing out the products, they were very grateful and interested in the topic, and it was really great seeing that,” she said. “Talking about menstruation isn’t very popular there, but I just wanted them to know that it’s normal and it’s not something to be ashamed of or something they should hide. I wanted them to know that they not only have support in Bangladesh, but also from us at Period Project.”

This year, Rosaleen and Pazokian hope to expand their organization’s reach to Title I schools in Durham County and surrounding areas. “We’ll definitely be focusing on Wake County, but we also want to focus on schools that have that economic need, not just the hygiene need,” said Pazokian.

“In October, we’re going to have our first period education day. We’re going to go to an elementary school to teach them about menstruation, what to expect and give them little packets. I think it’s going to be very helpful because the younger you learn about it, the less surprised you’re going to be, and the less change you’re going to feel,” she added.

The founders still think more needs to be done in order to fight period poverty.

“The stigma is especially evident in the fact that we don’t provide tampons because it would lead to backlash. If we get bigger and become more established, I’d like to provide tampons but right now, we’re still small and I want schools to trust us as much as possible,” said Pazokian. “Some type of product is better than nothing.”

As the organization strives to expand its reach, it continues to provide period products and support students in need.