In the first months of the 2023-2024 school year, school administrations have seen an increasing trend in overheating classrooms that reach soaring temperatures. Some have chosen to dismiss students early, citing significant detriments that disrupt student success. Green Hope High School faced similar challenges on the first day of school, when HVAC system failures caused classrooms to reach temperatures of over 100° F and school administration dismissed students halfway through the day.

Various experts have expressed their concern over the potential implications that poorly maintained HVAC systems could have on student health.

Jordan Clark, a Duke postdoctoral associate at the Heat Policy Innovation Hub explained that badly maintained HVAC systems would harm students’ health. “Extreme heat conditions and inadequate HVAC systems can markedly impair student performance and health,” he said. “Elevated indoor temperatures, exceeding 78-80°F, have been linked to reduced cognitive function, leading to decreased learning abilities and academic performance.”

Air quality is another major concern in maintaining school HVAC systems; broken ones can put students and staff at high risk of increased pollutants in the air. He explained that properly maintained HVAC systems lower the concentration of carbon dioxide and volatile organic compounds in the air, and as heat waves drive people indoors, maintaining these the air quality becomes even more important. A myriad of health risks – including headaches, fatigue and nausea – could occur if the issues aren’t resolved.

He further expressed his concern that the issue could worsen due to global increases in temperatures. The effects of climate change extend the hotter weather typical of summer months into earlier spring and later in the fall, which impact schools more than it previously did. “As temperatures continue to rise, and extreme heat events become more frequent, the need for efficient cooling systems will become even more critical,” Clark said.

Clark posed that for schools without proper HVAC systems, this may even prompt school starting and ending times throughout the year to change. “[This] may result in significant changes to the traditional timing of the school year, which has aligned with cooler parts of the year,” he said. “Schools may be forced to start later in the fall and end earlier in the Spring, which presents numerous challenges.”

Green Hope Principal Mrs. Alison Cleveland said that school administration retains few rights to control the quality of HVAC systems in schools. “Outside of things like providing fans through[out] rooms and constantly monitoring the temperature, communicating with central office and maintenance to figure out what’s the threshold that is too much where you were teaching and learning can happen outside of that,” she said. “[We] don’t have any specific procedures. [We’re] just monitoring and doing our best to keep rooms cool.”

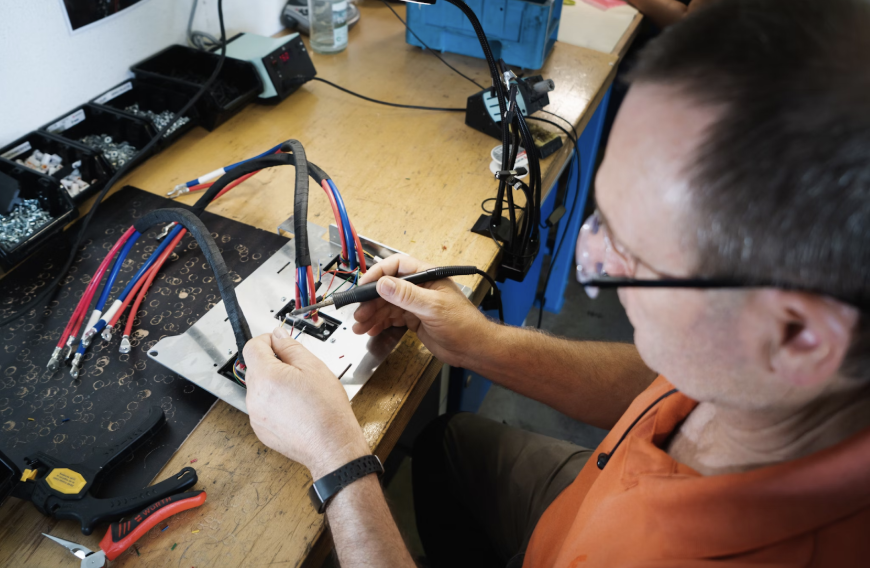

Although school administration regularly monitors the HVAC systems of the school, they have no power to update or replace them with new ones. “We can check it, we can monitor it and we can report it and that’s what we do. As much as we can,” she said.

However, administrators are tasked with making the decision of what temperature to maintain classrooms at and when to send students home – decisions that take a long process. At the time this article was published, the Wake County Public School System did not mandate certain temperatures for classrooms. The North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (NCDPI), however, published a guide named “High Performance Guidelines” in 2012 that detailed classroom air quality, HVAC system and water efficiency suggestions for schools. In regards to internal school temperatures, the guide advised, “Generally, indoor spaces are perceived as comfortable with temperatures around 68-76 degrees and humidity about 40-60%.”

In making decisions of when to close down the school, Mrs. Cleveland emphasized the complexity of making such decisions. “There’s not a specific threshold, and no decisions made by one person. It’s a collaborative decision. We work together with maintenance and operations, our facilities, Superintendent, transportation, so there’s a collective decision based on what [and] how bad [it is],” said Mrs. Cleveland.

Clark explained that the people with the most power in this process are state and federal policymakers, who can draft legislation that mandate frequent HVAC system checks and better funding. “Cultivating a preventative maintenance culture is vital, where potential issues are identified and rectified before escalating into severe problems, thereby conserving resources in the long term,” he said. Preventing the problem is critical, rather than waiting around for systems to break. “Ensuring swift access to existing funds is crucial to address emergent issues promptly.”

Such legislation would remain imperative to improving equitable access to functioning HVAC systems for schools in low-income communities. “The schools that are well-funded generally have better infrastructure, including more advanced, or any at all, HVAC systems and better insulation,” said Clark. “This disparity could exacerbate existing educational inequities as students in under-resourced schools may face more frequent disruptions to school days and health issues owing to inadequate heating and cooling systems.”

In the long-term, Clark also emphasized the importance of sustainability in HVAC systems. “Moreover, schools should adopt a comprehensive approach to sustainability, encompassing optimized energy consumption, the utilization of renewable energy sources, and efficient water management,” he said.